Diego Rivera immersed himself in his art: in simplicity and form—in colors and culture—in the “what” and the “why” of society and science. Rivera, accompanied by Ariel Guzik, conceived a work of art, El Agua Origen de la Vida, which portrayed all of these ideas. By integrating the natural science of the biological world and Mexican culture: a masterpiece was made.

From an educated and well-versed Mexican family, Rivera studied art and form throughout his childhood and into adulthood in Mexico and Europe[1]. He aimed to capture the viewer—to create a pure and simplistic art that could reach a broad audience. As a Marxist, social politics drove Rivera’s art—within his work, he analyzed the disparities between the rich and poor to illustrate the hardships that working class people faced[4]. Rivera adopted frescoes and murals because of this interest in social disparity—he wished to have his art be accessible to all, no matter their social class, and felt that it was his duty as an artist, and an intellectual, to publicize his art. Murals were a key part of this idea because they allowed Rivera’s art to be readily available to the population.

Rivera travelled to the US in the early 1930s and propagated the importance of creating culturally relevant public art[2]. After doing numerous murals in the US, Rivera returned to Mexico and continued to promote these public works for the Mexican people[2]. Of his many murals, El Agua Origen de la Vida is especially unique due to its sheer size and grandeur. Commissioned by the Cárcamo Water Works, El Agua Origen de la Vida was intended to emphasize the beauty and significance of water[4].

Water has long been an issue in Mexico—to provide sufficient water to large cities like Mexico City, thousands of rural Mexicans have been displaced to allow the creation of dams. For centuries, Mexico has faced issues with clean and reliable water[2]. Understanding the importance of water and its widespread effect on Mexicans—poor and rich alike—Rivera started working on El Agua Origen de la Vida. The work produced however, is much more than a commission; it is monumental, quite literally. Rivera fashioned a massive fountain which depicts an Aztec god[1] that guards the home of the murals: just beyond its poised head lay the doors to the Lambdoma Chamber, leading to El Agua Origen de la Vida.

The Lambdoma Chamber is an architectural feat in and of itself, though credit cannot be given to Rivera alone; Ariel Guzik, another Mexican artist, designed the chamber[2]. Guzik worked with Rivera to cultivate the idea of water and its representation in Rivera’s piece. The Lambdoma chamber was designed to amplify and conduct the sound of rushing water and fill the ears of spectators. The chamber was a success. What the audience feels as they enter the room is much more than any traditional presentation: the combined structures engulf viewers’ senses and takes them on a unique experience. What was created allows pure serenity and awe, woven deep into the tissues of the body. It embraces the viewer not only in its sound—but also through the vivid masterpieces of Rivera.

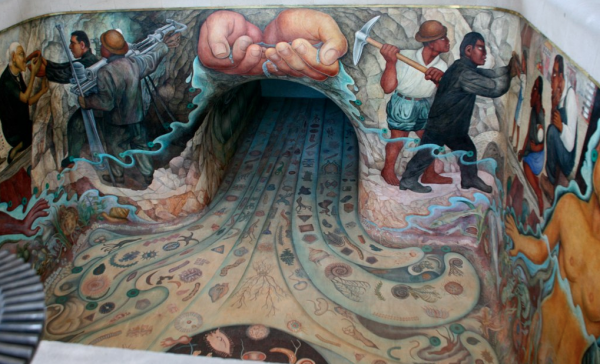

Within the chamber lies an open pit in which Rivera’s murals have been mapped out along the walls and floor. Collectively, El Agua Origen de la Vida is an expansive unification of life—the biological—and the Mexican people—the cultural. One of the four walls contains a massive hole that represents the source of water, and therefore, life itself. The lining of the tunnel is coated in atoms and algae that flow into the pit entwined into the water. These biological foundations lead the way for more complex crustaceans and sea life that then rise up the walls and spill into the intricacies of society.

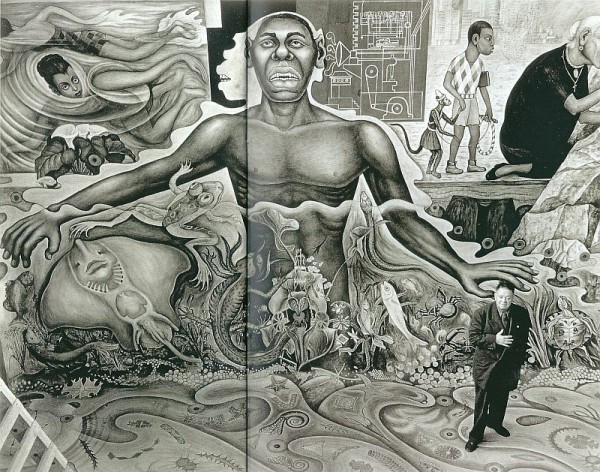

A man and woman stand naked—their bodies strong and brazen—in the centers of opposing walls. Sea creatures crowd around their bodies representing health and fertility. Both are painted in a primitive manner, contrasted with the modern people set in the background. This man and woman claw at a simpler but distinct time, while also signifying that the water they are encapsulated in, is the basis for their existence. Notably the woman is wearing turquoise earrings and the man has similar turquoise rings lining his body. These turquoise ornaments are stylistic of Mayan Indians who originally inhabited Mexico[4]. By including them, Rivera alludes to the basis of modern day Mexican culture.

At the mouth of the tunnel, miners can be seen distributing water to a family, who symbolize the working class of Mexico, and an older, religious woman, who represents the bourgeoisie. To the right of the central man and woman, a family working on their crops, and young adults swimming and showering can be seen. Rivera, who was deeply devoted to his social beliefs, often depicted hard working class people in his paintings[2]. These people were used not only to emphasize disparity, but also to evoke familiarity—tapping into the cultural identity of Mexicans alike. What Rivera illustrated was the epitome of the ideal hard working family—something that people could relate with.

On the wall opposite the tunnel Rivera added a dedication to the builders of Cárcamo. Lined along this wall is a group of men working with blueprints[2]. Rivera made each man looking up above the mural, as if they are aware of the passerby above him. This added even more surrealism to the piece—connecting it that much more with the audience.

Rivera intended to connect with his cultural ancestry and with the Mexican people. To say he accomplished this would be an understatement. In Rivera and Guzik’s exhibition what was created was a monument glorifying both water and the Mexican people. By uniting images and sound, science and society, life and growth—Rivera and Guzik created a masterpiece—a symbol that will stand for the Mexican people and the water that has sustained them for centuries to come.

CB

Work Cited

[1]Beaubien, Jason. “Unusual Diego Rivera Work Restored in Mexico City.” NPR. NPR, 21 Dec. 2011. Web. 15 July 2015.

[2]Cárcamo de Dolores, El Agua Origen de la Vida, Cárcamo Water Works

[3]”Diego Rivera Biography, Art, and Analysis of Works.” The Art Story, n.d. Web. 14 July 2015

[4]Mataev, Yuri. “Olga’s Gallery.” Diego Rivera. Biography. ABC Gallery, n.d. Web. 14 July 2015.